January 12, 2022

French Designer Audrey Large Aims to Challenge Perceptions of Reality

“To me, the dichotomy between digital and material is irrelevant.”

Audrey large

Do you have any immediate thoughts or reactions in terms of how the metaverse can impact art and design?

Hito Steyerl very much inspires my research. Like her, I believe that we are not going towards the total dematerialization of ourselves and our surroundings but instead become more and more material. But materialized in another kind of way. I think that it is a very important question that is left in the hands of the object designers—those that design our closest surroundings. My work navigates these questions.

The metaverse is a continuity of what we are living now. Beyond obvious concerns about control and data, the pitfall of this would be to think about it as a better version of our materiality, as a reality-to-be-lived instead. The other problem is to design the digital world as a representation of our material surroundings. This is the problem with simulation, it leaves us with weird feelings and it never totally fits—we can’t totally live it.

My work uses the computer as a space with its own rules, not as a space for the simulation of the real. It helps me to rethink a different kind of materiality. If the metaverse really happens—and it is already happening—it should be thought of and designed hand in hand with our physical surroundings to be experienced as a whole—materially and digitally.

You’ve mentioned in previous interviews that you design objects like others design images. What do you mean by that?

My work responds to the exponential digitization of our surroundings. To me, the dichotomy between the digital and material is irrelevant. There are a lot of theories about the materiality of images, and on the other hand, I am wondering about the image properties of objects. This could be through rethinking our object design methodologies in the lens of image fabrication processes—CGI, digital cinema, computer vision, etc.—are interesting fields to rethink ways of manipulating matter.

You recently had a digital exhibition through Nilufar Gallery. What was that experience like and how does the role of objects shift when they’re only available to interact with in digital space?

I find it deceiving when digital exhibitions try to recreate physical ones, when they are used as a solution to the inability to exhibit in real life, as we saw during the pandemic. At the same time, the situation helped [artists and designers] consider a new way of exhibiting that was already there but rarely [utilized].

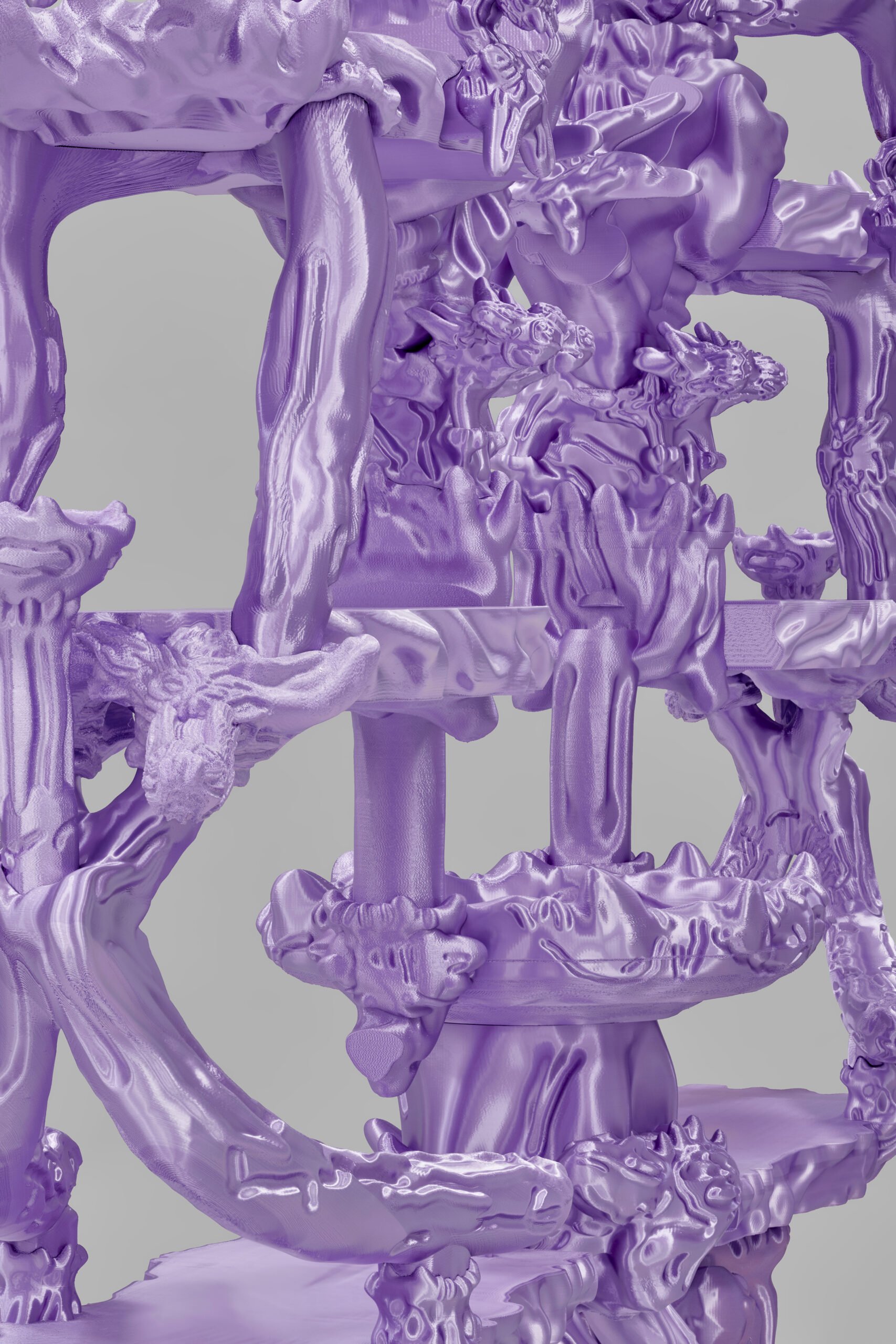

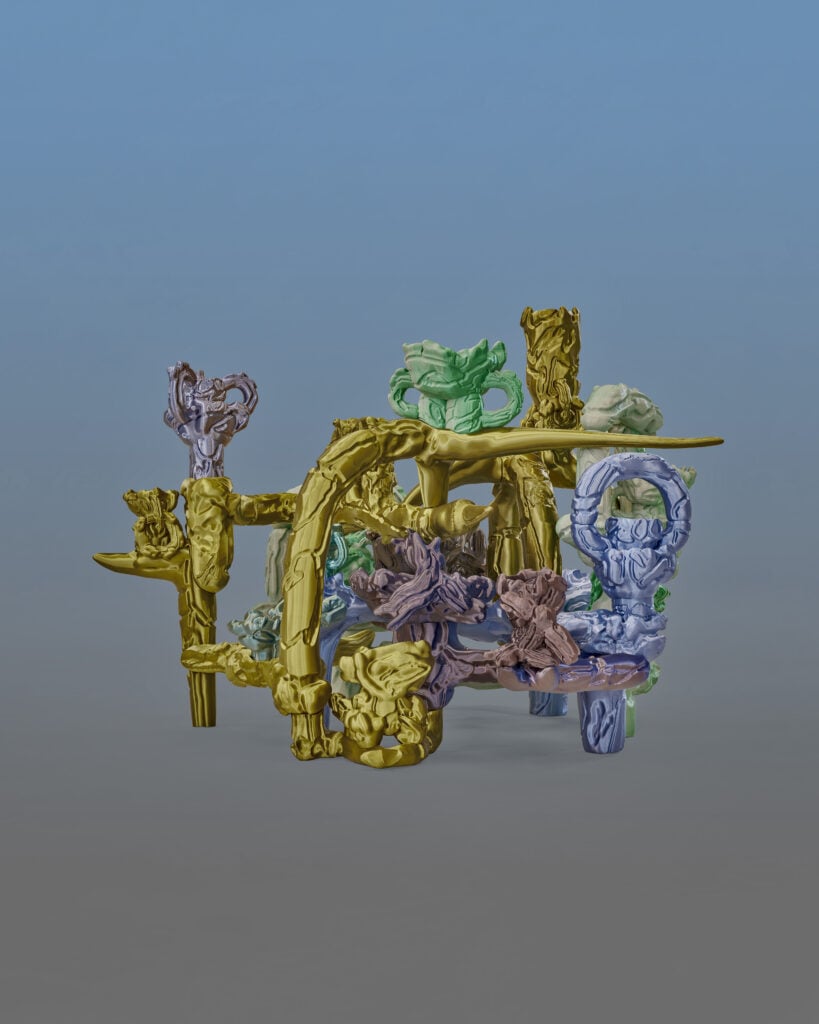

I was commissioned to make an online exhibition by Nilufar Gallery called Scale to Infinity. To me, it was important to not create a representation of a physical show but to think about this project with its own set of rules. In the case of my work, a digital platform stands halfway in between a repository of latent digital files waiting for future materializations, and a diorama, or a representation of their closest original environment.

What was interesting for me was that the online display can place the viewer closer to my working process: They can interact firsthand with the crafted files from which the 3D printed objects will, later on, be materialized—files that are often hidden.

In tandem with Scale to Infinity, you had a physical exhibition at Nilufar titled Some Vibrant Things. In it, you allude to the concept of “Vibrant Matter.” Can you expand on this?

My work mainly aims at challenging our perception of the real. Everyday objects represent a relevant place to do this. Functionality is a sign loaded with history, a pretext of proximity with the viewer, a space to create tension in between what we know, what we don’t bother questioning, and what we are looking at. In that sense, I am moved by the question of surface and its potential to be a fictitious and ambiguous substance upon which reality, as well as hyperreality, can be located.

The term vibrant matter refers directly to Jane Bennet‘s research and to [what she calls “vital materialism”]. This line of thought is very interesting to me because rethinking [objects] and matter as active, lively, and in relation [to us] is in opposition to our traditional western view as matter as passive.

In a digital context, matter is fluid too, it is meant to travel and transform in between formats. I like to think about files as carriers and containers of potentialities. In my work, this state of becoming manifests itself on different levels—in the way matter reveals itself to the eye through shiny iridescent surfaces, in the process of making and treating matter (from drawings to 3D models to 3D prints back to drawing, etc.), and finally, in the way of envisioning matter and objects. Both the files of Scale to Infinity and the physical objects of Some Vibrant Things act as examples of this.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

Spanish Firm ERRE Is Quietly Transforming the City of Valencia

With recent commissions from Marriott and Andreu World, as well as a new arena designed with HOK, ERRE is at the forefront of the city’s development.

Profiles

Emergent Vernacular Architecture Studio Builds for Community Resilience

From Haiti to Lebanon, the London-based studio helps create public spaces for those that need it the most.

Projects

Inox, Light, and Fight

At Laguna during Mexico City Art Week, fifteen architecture practices confront scarcity head-on, framing reduction, reuse, and resistance not as aesthetics, but as the operative conditions of contemporary practice.